Understanding the Tools That Shape Us

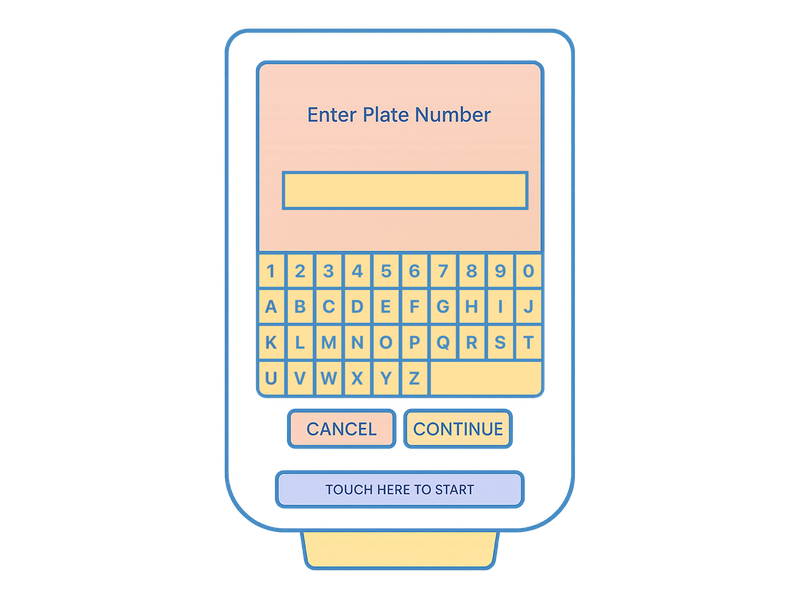

A few weeks ago, I went to use a parking machine and the keyboard was alphabetical rather than QWERTY layout. I’m standing there trying to find the right letters for my number plate and it’s taking forever. Meanwhile, I’m watching my 5 year old son go half way down the street. I’ve used a QWERTY keyboard for 30 years, so I can type without looking. But give me an alphabetical keyboard and it slows me right down, particularly when I’m distracted.

This parking meter keyboard is an example of terrible UX. But that’s not the point of this story. I’ve been experimenting with AI since it launched to see how it can help optimise the way Smudge designs software. So, I thought this keyboard design could be a good test for AI. Maybe AI could design a simple interface like this better than humans.

I uploaded a photo of the parking meter to ChatGPT and said, “How could this be improved?”

ChatGPT said, “This parking meter interface could be improved by optimising the keyboard layout and text visibility.”

I said, “I agree. That would help. What else?”

Then ChatGPT went on to say, “The current QWERTY style keyboard is compact and may cause input errors. A larger, clearer keyboard would help.”

And I thought, wow, ChatGPT! We have an issue. What's going on here?

I'm pretty sure ChatGPT compared my photo to its vast image bank, concluded the image showed a parking meter keyboard, and assumed it was a QWERTY keyboard because almost all English language keyboards are QWERTY. It wasn’t until I asked ChatGPT to list the keys on the keyboard that it identified we were dealing with an alphabetical keyboard.

This little incident gives us many insights into AI. It’s important to understand how AI operates and to know its limitations. It also helps to know that AI doesn't attribute meaning to nuance in the same way that we do. And it’s a lesson in how to use prompts to overcome these shortfalls.

Habit trumps intentional design in many areas of our life

After my parking meter keyboard experience I researched how the alphabet and the QWERTY keyboard came to be the way they are. And I found that the English alphabet organically evolved into its current order. It wasn’t logically designed. In addition, we inherited the QWERTY keyboard layout from typewriters, where frequently-used keys were separated to stop them jamming. Now we have computer keyboards, there’s no logical reason for the QWERTY layout, but it’s what we’re used to. Understanding familiar patterns and building on them is an important part of good design.

Are we making logical design choices about the tools we’re making available to our teams and families? I don't want the people around me hooked on OpenAI tools simply because they’re becoming the dominant LLMs in the market.

AI tools are becoming critical infrastructure. Should that knowledge and infrastructure be privately owned? For example, government policy could prioritise using open-source AI models in so we aren’t learning OpenAI’s interface as the AI default. That strategy feels more in the New Zealand public interest than supporting tech with private interests at the core.

I'm passionate about this topic because I care about people being in control of their own destiny. I know how technology works and I know how big companies work. We should be actively considering the consequences of entrusting big tech to “think” for us.

Many New Zealanders are using AI tools every week

But AI is an opaque, black box for many people. We don’t understand how AI tools work. We don’t understand AI tools’ weaknesses. We simply accept the answers they’re given and marvel at these tools without question. I catch myself going to use a tool that I personally experience hallucinations in frequently, and thinking well that answer sounds good enough for me today.

Last month I wrote about the limitations of AI. AI lacks clear standards. AI tools offer advice on any subject without oversight or accountability. There’s no guarantee the information provided by AI is accurate. AI tools have other shortcomings but AI companies don’t state how their tools can best be used. There’s also a lack of transparency around how AI models are trained. Finally, AI comes with the values, assumptions, and political bent of its makers and the data used to train it baked in. In short, tech isn’t always a benign influence.

It’s concerning therefore that our AI naivety levels are sky high. Many people don’t understand how AI tools work, or what LLMs do well. The narrative today that AGI is just around the corner feels the same as the ubiquitous predictions of autonomous vehicles, or a blockchain currency will replace traditional money.

In society, we rely on public systems being built with our collective wellbeing and benefit at heart. That may be a reasonable assumption in the public realm but when we take that belief into the world of private enterprise, it becomes naïve. Misconceptions that private enterprise is there for our benefit become risky when you’re dealing with a tool as influential as AI.

Banning AI tech isn't the right answer

Prohibition doesn’t work. Whether you veto alcohol or ideas, a ban doesn’t stop people accessing these things, it simply makes them more difficult to access.

Nor does regulation solve many of these AI issues. Regulation takes so much time to evaluate and change (which is a feature), the new innovation has already established normal ways of operating.

AI is here whether we like it or not. We can’t ban this new wave of AI tech. Regulation is only helpful to a point. The best answer is education. We have to educate people to use AI wisely and we have to do it well.

What are the practical things that we can do to educate on AI?

After grappling with this alphabetical keyboard trying to keep up so I could keep up with my son I was reflecting on what artifacts we are creating today like the order of the alphabet that future generations will take as their familiar and learnt patterns.

I remember the day that the local police came into my school, taught us how to ring 111 and ask for the emergency services. That’s an example of giving kids skills for the future.

But the skills we need for the future look very different to those we’ve traditionally focused on. What does it look like to build a baseline understanding of how AI tools work, what they’re good at, and where they fall short? How do we create the space—across workplaces, communities, and education—for more people to engage with the ethics, assumptions, and implications of these technologies?

This isn’t about training people to use specific tools. That approach just reinforces dependency on whichever company currently dominates the market. Instead, we need to foster critical thinking about technology itself—how it’s built, who it serves, and what choices we’re making by using it.

When I did PE at school, I was taught how to play different sports, when I really needed physical education for life. It would have been more helpful to understand how my body works, how to move it, nourish it, and rest it . Similarly, we need to help people understand issues around ethics, data protection, and AI to give people a better chance of making educated decisions when and how they use digital tools.